The world of TV planning and buying has never felt so upside down. Nielsen, long the accepted gospel for television viewing data, has had a series of high-profile stumbles and industry rifts in recent months and years, including the loss (and eventual reinstatement) of its accreditation by the Media Rating Council, their last-minute return to panel-only TV ratings for this year’s upfronts, their refusal to work with OpenAP’s Joint Industry Committee, and even their admission that their initial ratings missed two million viewers in its initial rating of this year’s Super Bowl. That has created a rather large vacuum in the once reliable (if imperfect) world of TV measurement, leaving many in the space to wonder what exactly comes next for how TV is purchased and measured.

A Little Context

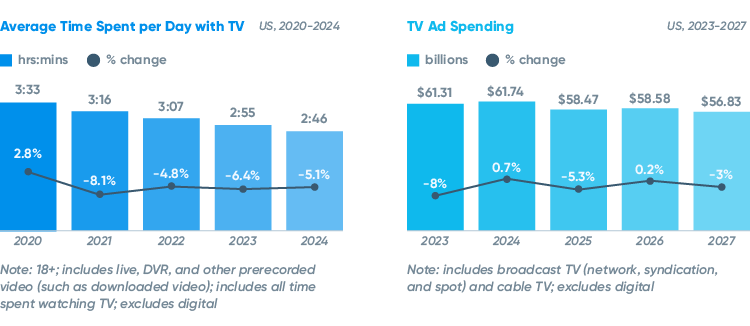

There’s a whole lot going on in the background of these headlines. Of course, linear (or offline) television viewing has been declining precipitously in recent years, particularly with younger viewers. Research from eMarketer predicts an overall decline of more than 25% in daily viewing from 2018 to 2024, with baby boomers now watching more than four times the amount of TV per day as gen z viewers. Albeit at a slightly slower rate, the dollars are declining as well. Linear TV ad spending peaked in 2018 at $72.4 billion. By 2024, that’s expected to fall to $61.74 billion– a decline of just under 15% (not adjusted for inflation, of course).

A Legacy of Limitations

So why all the drama around TV measurement? The answer to that question can be found in a legacy of limitations. TV has long been measured by survey panels across the country made up of households meant to be representative of the total population who share data about their media habits. Today, that panel is just over 40,000 U.S. households, according to Nielsen.

This methodology has made sense historically. There was no mechanism to understand how many people were watching a specific TV channel or program. When we talk about TV measurement, unlike online channels, the conversation is burdened by this history of abstraction. This counting of viewers was (and is) used to set rates for TV advertising for the upcoming cycle. That’s why you hear people talking about Nielsen as the currency of the TV space. Nielsen ratings have long been used to negotiate the annual upfront buying of TV inventory across the major networks. If the network fails to deliver the ratings, they are on the hook to makegood on the shortfall. If Nielsen isn’t the currency for this medium, then what is?

Why Are Things Heating Up Now

We’re at a tipping point with TV advertising. Spending on digital video has already surpassed spending on TV, and time spent with digital video surpassed TV long ago in the most coveted demographics, poised to surpass TV overall sometime next year. That means that dollars have long been flowing (albeit rather slowly) from TV to digital, and new norms are emerging. Digital media practitioners don’t think about an abstract currency for their buys because they transact based on real time delivery of things like impressions and clicks. While there are still lots of measurement challenges in digital, results are much more readily available and timely. Third-party ad servers validate digital metrics in near real time, offering the ability to optimize spend on cycles measured in hours, not months. You can target specific audiences, not just proxies like programming or dayparts.

Overall digital ad spending will top $260 billion in the U.S. this year, making it well more than four times the amount spent on TV. That means that media people are spending the strong majority of their time with channels that offer the opportunity for instant results and quick optimization. TV, with its legacy of limitations when it comes to measurement, feels more and more like the outlier. The efforts of many interested parties in this industry (including new measurement players) have focused on finding ways to bring TV measurement up to these standards, and the result is the messy place we find ourselves in right now.

The Complicating Factor of CTV

In the midst of all of these trends, we’re also seeing the meteoric rise of what we in the industry like to call Connected Television, or CTV. The term really just refers to streaming programming that’s viewed on a television screen (no one outside the marketing makes this distinction). Measured this way, CTV is the fastest growing major ad channel with growth of 21.2% in spend year-over-year. By next year, CTV households will be more than double the number of traditional pay TV households. This complicates things because CTV is both a digital channel and a form of TV. As such, it is purchased by both TV and digital teams who speak different dialects of media jargon and carry around different sets of expectations on the buying process and the availability of data for targeting, measurement, and optimization. The same is true for the CTV streaming services themselves. Many are the products of legacy TV providers, while others look more like tech startups than media companies. As such, they are not inclined to adopt the same standards and expectations.

What to Do About TV Measurement

While it’s undoubtedly a medium in decline, all signs point to linear TV continuing to be a significant channel for many years to come. Given the above factors, the most constructive path forward is simply to recognize that linear TV is different and treat it accordingly. Given its lack of direct addressability and measurability, TV will need some kind of currency. Those who buy TV will need to accept that Nielsen will not be the only (or even the de facto) choice going forward. It will be up to each brand to decide what works best for them. Standards like the ones that OpenAP’s Joint Industry Committee have proposed can be a useful framework for helping all of us navigate this new reality as effectively as possible. They can also be useful for helping us to look at cross-channel measurement and channel-level optimization.

However, there is one big pitfall that we all need to avoid, and that is treating other channels the same way we treat TV. We do not need currency to buy CTV or any other kind of digital video. We can use the same data and tools that we use to buy every other online channel. It is counterproductive to continue to drag the legacy of limitations associated with TV into this new world. CTV, just like other digital channels, gives us the ability to see results quickly, make optimizations, move budget around, garner fast insights, explore innovative ad formats, and improve performance in the moment. All involved will be poorly served if we don’t take full advantage of these inherent advantages.

In other words, TV measurement might be a mess right now, but let’s not sweep it into the next room.

To learn more about the rapidly evolving video and television landscape, connect with our experts.